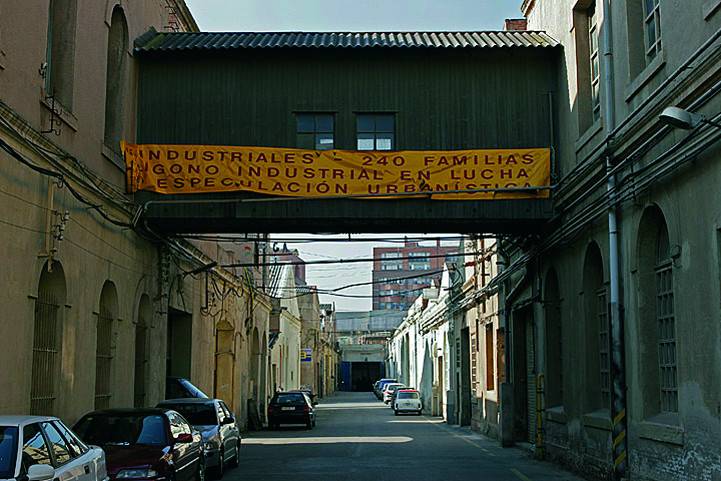

Can Ricart , 2004

For decades, the former industrial neighbourhood of Poblenou was subject to one of Europe’s largest urban redevelopment schemes. In the year 2000, Barcelona’s metropolitan government accepted the 22@ plan. The urban regeneration scheme aimed at transforming the industrial area of Poblenou into THE technology and innovation neighbourhood of the city (or even Europe while they were at it), and at the same time increase space for housing and leisure.

As part of it, French architect Jean Nouvel was asked to transform a 5-hectare piece of land into a ‘Central Park’. Right after the scheme was adopted the metropolitan government started expropriating houses on site with the last ones demolished in 2003.

A year later the site was still vacant. Users of the factory-building and local residents took matters into their own hands and started to build their own park. Initially, the factory walls were painted. Then, on 29 May 2004 action ParcCentralPark followed.

Meanwhile, the old factory complex still housed about sixty SMEs, collectives and arts centres. Together they employed two hundred and forty people. Among them was Can Font, a space shared among others by City Mine(d). When in September 2004 the metropolitan government informed users of imminent demolition of the complex, the platform “Salvem Can Ricart” (Save Can Ricart) was founded. It initiated campaigns like Made in Can Ricart to promote products made on site. At the same time experiments with virtual public space took place in Cityborg

By April 2005, the platform developed a dossier in defence of the site: “Can Ricart – Parc Central Nou Projecte” (Universidad de Barcelona, 2005). In it, its heritage value was emphasised –one of the last three remaining 19th century industrial complexes in Barcelona, in which textile, soap, paper and more recently creative industry took over from each other¬–, its urbanistic importance was explained –a publicly accessible site on which industry and experiment co-existed– and a critique of the 22@ scheme was articulated –the plan interpreted innovation too narrowly leaving only room for technological innovation.

More importantly, the dossier contained an alternative proposal made by the citizen platform that combined existing qualities with ambitions from within 22@. The campaign garnered enough media-attention to re-open negotiations, which would carry on for month. In January 2006, the metropolitan government decided to preserve half of the industrial complex, and to adjust the plans according to users’ needs. Unfortunately, the news arrived precisely the day on which the publican of Bar Pacos, the last remaining meeting place on suite, was evicted. With it, the site lost much of its public character, despite the fact that a decade later small enterprises and an arts centre were still present.

Related: